Launching the recruitment for participants of the NUA study in Nova Gorica for April/May 2025! Sign and and help up shape mental health and well-being!

Category: Nature & Mental Health of communitiers

Nature in Mind: Interview with Dr. Bruno Marques

Dr Bruno Marques is a landscape architect and educator. He completed his Landscape Architecture studies at the University of Lisbon (Portugal) and Berlin Technical University (Germany), followed by his PhD studies at the University of Otago (New Zealand). Bruno has practised in Germany, Estonia, the United Kingdom and New Zealand, having an extensive portfolio of Read More

Nature in Mind: An Interview with Erin Sharp-Newton

Erin Sharp-Newton, M. Arch, is the 2024 President for the American Institute of Architects Central New Jersey (AIACNJ.org) and serves as the Director of the Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health (UD/MH), founded by Dr. Layla McCay. She has been a Fellow of UD/MH since 2016 and holds the role of Section Editor of Read More

How Urban Design Can Impact Mental Health & Well-being

Our cities are often designed with function in mind. We build parks for exercise, wider sidewalks for pedestrians, and bike lanes for commuters. While we have made progress towards building healthier bodies, we have overlooked the equally important mental well-being. Urban design has a powerful influence on the quality of its citizens’ life, especially mental Read More

Mental Health in Slums – the Case of Bangladesh Among Other Developing Countries

The share of the world’s population living in urban areas has been predicted to increase from 55% in 2018 to 60% in 2030 (UN, 2018). Every year people move to the urban areas from villages for various reasons. If we try to see this urban-rural migration under the push-pull model, push factors from rural end Read More

Urban Land Institute/Health Leaders Network

In early 2021 our Board Member and Lead researcher Dr Diana Benjumea was selected to join a prestigious Health Leaders Network initiated by the Urban Land Institute (ULI). Health Leaders Network is a platform aimed at sharing knowledge and ideas with health leaders across continents. It gathers professionals across the globe with the skills and Read More

Networks of Nature: Integrating Urban Farming in the city Fabric

Our programme Planting Seeds of Empowerment Mental Health and Well-being of the Communities starts this year with a new project created in collaboration with international organisations to emphasise the importance of nature in the mental health and well-being of people residing in heavily urbanised cities. The project entitled: Networks of Nature Integrating Urban Farming in Read More

Policy Briefs – Urban Health and Wellbeing Programme by Springer

In our most recent contribution to the Volume Two of the book series Urban Health and Wellbeing Systems Approaches, published by Springer and Zhejian University, we discuss the preliminary findings of our research project currently conducted in low-income communities in Medellin Colombia for our program Planting Seeds of Empowerment: Mental Health and Wellbeing of the Read More

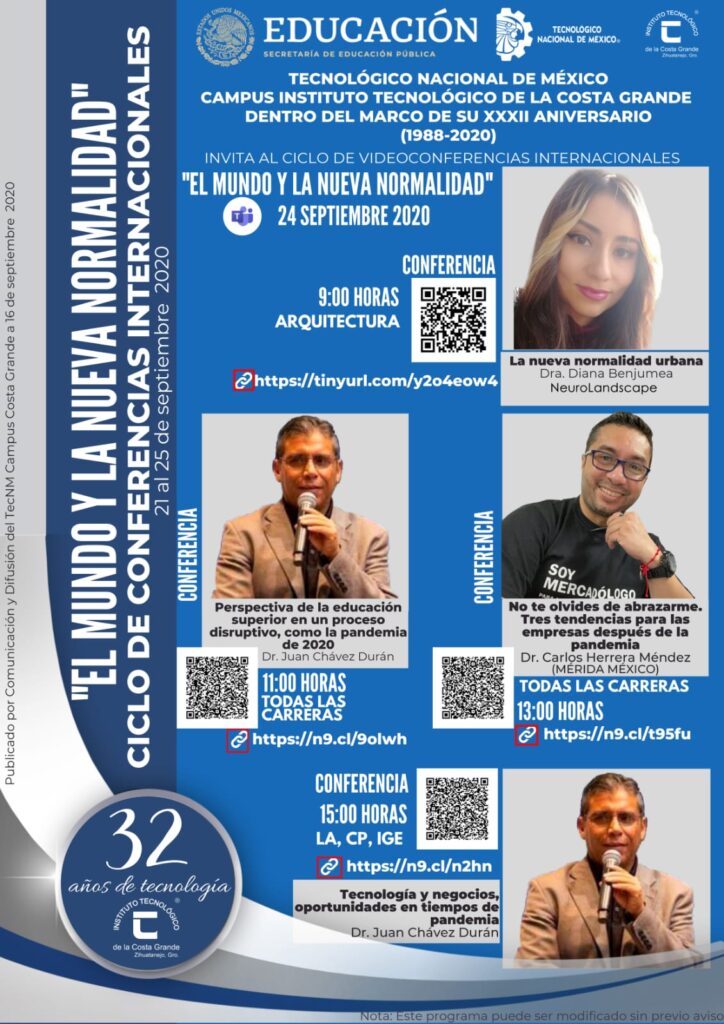

The New Urban Normal_Dr Diana’s speech at TecNM (Mexico)_VIDEO

24th September 2020. Tecnológico Nacional de México, campus Costa Grande, hosted an online event addressing the World New Normal in the interdisciplinary lens. Dr Diana Benjumea gave a speech regarding architecture and urban planning, where she sets a new paradigm of bottom-up, evidence-based urban design. Moreover, she introduces NeuroLandscape projects and explains the global implications Read More