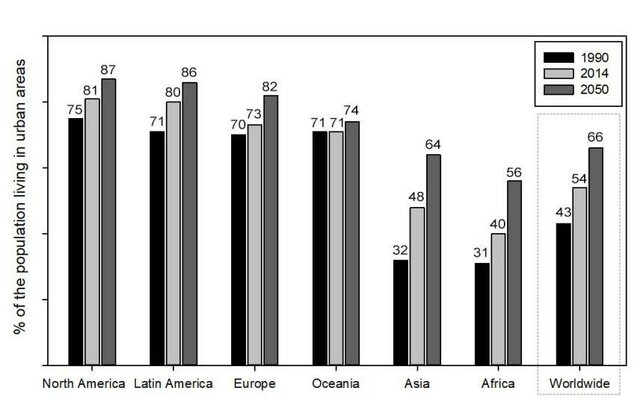

Our cities are often designed with function in mind. We build parks for exercise, wider sidewalks for pedestrians, and bike lanes for commuters. While we have made progress towards building healthier bodies, we have overlooked the equally important mental well-being.

Urban design has a powerful influence on the quality of its citizens’ life, especially mental health. It shapes the spaces where we live, work, and interact with others. From the soothing presence of green spaces to the efficiency of street layouts, the built environment affects our daily mood and overall well-being. Well-designed urban areas can foster a sense of community and belonging, providing places for people to connect, be active, and recharge. However, poorly planned environments can contribute to feelings of stress, anxiety, and isolation. By understanding the relationship between urban design and mental health, we can create cities that not only meet our physical health needs but also nourish our mental health.

![]() Disconnection from Nature

Disconnection from Nature

Urban environments often disconnect residents from nature, which is deeply rooted in our evolutionary history. Humans have evolved in natural environments, and the lack of green spaces and natural ecosystems in cities can lead to residents developing what is referred to as “nature deficit disorder.”[i] Urban residents lack access to nature’s psychological benefits, such as reduced stress, improved mood, and enhanced cognitive function [ii], [iii]. Research on anxiety disorders (such as post-traumatic stress disorder, distress, anger, and paranoia) and the risk for developing schizophrenia showed higher rates in urban versus rural areas [iv]. In fact, epidemiological studies concluded that the more time spent in an urban environment as a child, the higher the risk for developing schizophrenia as an adult [v].

![]() Noise Pollution

Noise Pollution

Constant exposure to noise pollution from traffic, construction, and industrial activities can seriously impact mental health. Humans are not adapted to endure continuous loud noises, which can lead to chronic stress, sleep disturbances, depression, and increased anxiety [vi].

![]() Air Pollution

Air Pollution

Air pollution not only contributes to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases but also affects mental health [vii]. Long-term exposure to polluted air has been linked to cognitive function decline and an increase risk of developing mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety, and even dementia.[viii] The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that air pollution is responsible for approximately 7 million premature deaths per year, and a considerable percentage of these are in connection to mental health effects [ix].

![]() Traffic

Traffic

Heavy traffic and long commutes in bigger cities lead to mental exhaustion, stress and decreased life satisfaction [x]. The daily grind of tackling the morning and post-work rush hour adds to mental strain, leading to irritability and anxiety. A study from the American Journal of Preventive Medicine found that longer commutes are associated with higher levels of stress and lower levels of life satisfaction [xi]. Not to mention that traffic also increases exposure to noise and air pollution, adding to the detrimental effects on mental health [xii]. Living close to traffic can also disturb sleep patterns and cause further irritability and potentially aggression, which then fuels mood and anxiety disorders [xiii].

![]() Overcrowding

Overcrowding

High population density, often associated with large-scale, closely packed buildings, can lead to feelings of claustrophobia, stress, and social isolation. Overcrowding reduces personal space and increases competition for resources. This can lead to social tensions and a higher chance of (violent) conflict [xiv]. Furthermore, urban environments with high population densities can overload residents with stimuli, leading to sensory overload, higher stress levels and an impaired cognitive function [xv]. These factors can harm mental well-being, especially since humans are not evolutionary adapted to such densely populated living environments [xvi].

![]() Overload of Stimuli and Information

Overload of Stimuli and Information

Modern cities are packed with static and dynamic elements, which are abstract in design, all connected by a complex web of infrastructure. The variety of forms, colours, and textures, in a dense environment, can overwhelm the brain. Tasks that are simple in theory such as navigating the city become mentally exhausting as the brain struggles to process the overload of information being thrown its way. Over time, the constant over-stimulation can lead to mental fatigue, which in turn may increase the risk of developing mood and anxiety disorders [xvii].

![]() Abstract Forms

Abstract Forms

Cities are made up of forms based on Euclidean geometry, including straight lines, circles, triangles etc. But these forms are rarely found in nature. Rather, nature is filled with amorphic and asymmetrical forms. Research has shown that high exposure to abstract forms, like those in plentiful supply in modern cities, can feed feeling of unease and detachment, leading to increased stress and reduced mental well-being. On the other hand, exposure to natural elements does not have the same effect and can even reverse the strain caused by the urban structures [xviii].

![]() Shortened Visual Outreach

Shortened Visual Outreach

A key characteristics of city environments is the large-scale, high density of buildings and other built structures, packed into limited land plots. This places even more psychological strain on citizens as it creates the impression of a smaller personal space [xix].

How Urban Spaces Can Boost Our Mental Health

Well-designed urban spaces can have a transformative impact on our mental, physical, and social well-being. Research suggests that environmental factors in our surroundings can either exacerbate or protect us from the development of diseases, depending on our genetic makeup. The good news is that by creating optimal urban environments, we can not only enhance overall well-being but also potentially reduce the impact of genetic predisposition to certain health conditions. Our efforts should not stop at the doors of prevention (of mental health deterioration), but we should be striding towards taking action to improve mental health. So, what aspects should we consider when designing our urban environments?

![]() Green Spaces and Nature

Green Spaces and Nature

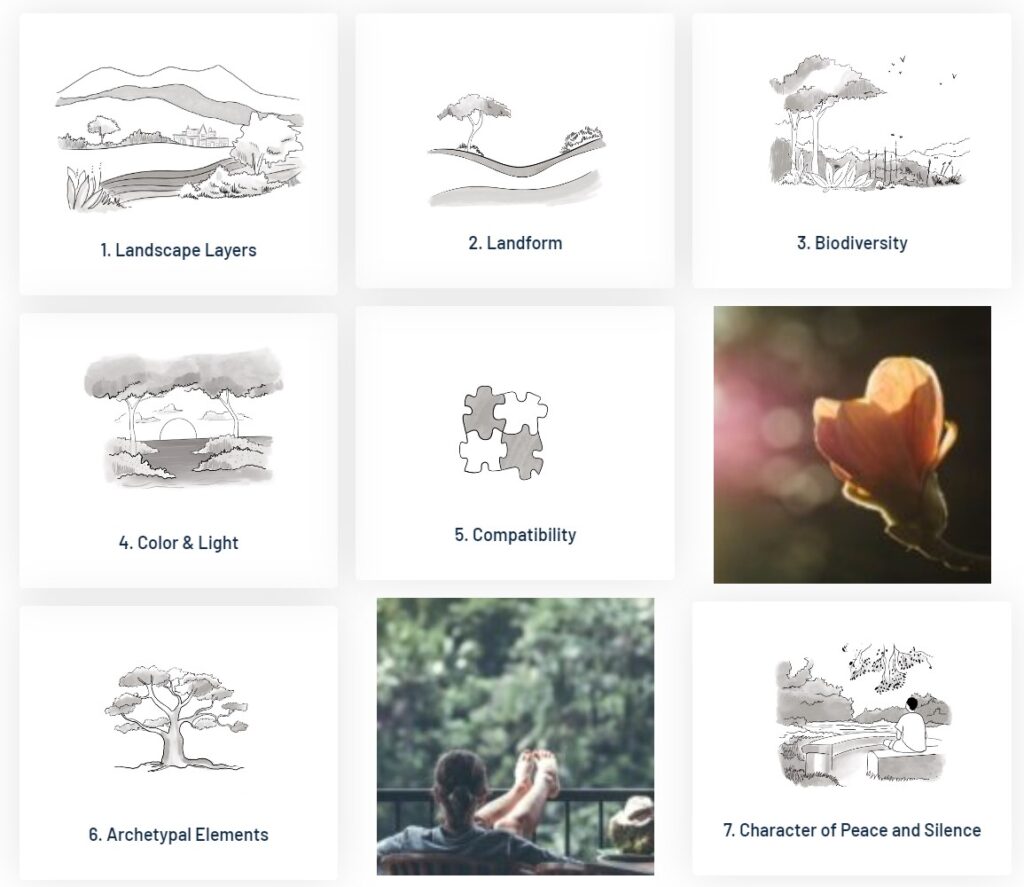

Providing free access to parks and other green areas is essential for not only improving but also maintaining mental health. Spending time in nature helps reduce stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms while boosting mood and concentration. Green spaces also promote physical activity, relaxation, and social interaction [xx]. Incorporating more green spaces such as community gardens curated with contemplative elements into city planning, we can counterbalance the negative effects of urban environments [xxi].

![]() Healthcare Accessibility

Healthcare Accessibility

Easy access to both mental and physical healthcare services is important for early intervention and continuous support. By reducing barriers to care, such as long travel times and exposure to elements that may negatively affect our health, we can improve overall well-being [xxii].

![]() Community Centres: Community centres offer social support networks, recreational activities, and educational programs that strengthen social cohesion and reduce feelings of isolation. These centres also provide safe spaces for individuals to engage in hobbies and group activities, fostering a sense of belonging and community [xxiii].

Community Centres: Community centres offer social support networks, recreational activities, and educational programs that strengthen social cohesion and reduce feelings of isolation. These centres also provide safe spaces for individuals to engage in hobbies and group activities, fostering a sense of belonging and community [xxiii].

![]() Inclusive and Accessible Design

Inclusive and Accessible Design

Designing flexible urban spaces that accommodate all ages and abilities ensures that everyone can enjoy public spaces. Inclusive design promotes social involvement and equity, which are crucial for community mental health [xxiv].

Implications for Urban Design and Directions

To take full advantage of smart urban design, we must prioritize the health of residents. Planners and policymakers have a key role in promoting mental well-being through thoughtful design. Therefore, consider the following recommendations:

- Integrate Nature-Based Solutions (NbS): Incorporating green spaces, urban forests, and community gardens into city planning can enhance mental health and help prevent (and treat) mental health conditions. Nature-based solutions reduce environmental stressors, encourages social interaction, and creates mentally supportive urban spaces.

- Implement Contemplative Landscapes: Design features that promote mindfulness and relaxation, such as depths in views, biodiversity in plant and animal species, harmonious, warm colours, shade and seating areas, water elements, can significantly reduce stress and improve mental health [xxv].

- Promote Social Interaction: Design public spaces that encourage social interaction and community engagement, such as "walkable neighbourhoods," community hubs, and recreational areas.

- Ensure Accessibility and Inclusivity: Urban spaces should be accessible to all, including people with disabilities, the elderly, and children. Inclusive design fosters a sense of community and ensures that all residents can benefit from public spaces. Inclusiveness should also be reflected in the design process, with active participation from users during development.

- Use Technology and Data-Driven Approaches in Design: Incorporate advanced tools like mobile Electroencephalography (mEEG) and machine learning to assess and predict the impact of urban design on mental health. This will confirm the changes that are to be implemented are indeed creating calming spaces that boost mental health and quality of life.

By prioritizing mental health in urban design, cities can become healthier, more resilient, and inclusive. When green spaces, accessible facilities, and safe, active areas are integrated from the start of the urban planning process—rather than as an afterthought—urban planner can create environments that ultimately improve the quality of life for all residents.

Authors: Annetta Benzar, Lara Renhe, Agnieszka Olszewska-Guizzo

References

[i] Olszewska-Guizzo, A., Fogel, A., Benjumea, D., & Tahsin, N. (2021). Sustainable Solutions in Urban Health: Transdisciplinary Directions in Urban Planning for Global Public Health. In Sustainable Solutions in Urban Health: Transdisciplinary Directions in Urban Planning for Global Public Health (pp. 279-296). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86304-3_14

[ii] Olszewska-Guizzo, A. (2018). Contemplative Landscapes: Toward Healthier Built Environments. Environment and Social Psychology. 3. 10.18063/esp.v3.i2.742.

[iii] Olszewska-Guizzo, A., Fogel, A., Benjumea, D., Tahsin, N. (2022). Sustainable Solutions in Urban Health: Transdisciplinary Directions in Urban Planning for Global Public Health. In: Leal Filho, W., Vidal, D.G., Dinis, M.A.P., Dias, R.C. (eds) Sustainable Policies and Practices in Energy, Environment and Health Research. World Sustainability Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86304-3_14.

[iv] Gruebner, O., Rapp, M. A., Adli, M., Kluge, U., Galea, S., & Heinz, A. (2017). Cities and Mental Health. Deutsches Arzteblatt international, 114(8), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2017.0121

[v] Vassos, E., Pedersen, C. B., Murray, R. M., Collier, D. A., & Lewis, C. M. (2012). Meta-analysis of the association of urbanicity with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin, 38(6), 1118–1123. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbs096

[vi] Hahad, O., Kuntic, M., Al-Kindi, S. et al. (2024). Noise and mental health: evidence, mechanisms, and consequences. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-024-00642-5

[vii] Bhui, K., Newbury, J. B., Latham, R. M., Ucci, M., Nasir, Z. A., Turner, B., … Coulon, F. (2023). Air quality and mental health: evidence, challenges and future directions. BJPsych Open, 9(4), e120. doi:10.1192/bjo.2023.507.

[viii] Power, M. C., Kioumourtzoglou, M. A., Hart, J. E., Okereke, O. I., Laden, F., & Weisskopf, M. G. (2015). The relation between past exposure to fine particulate air pollution and prevalent anxiety: observational cohort study. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 350, h1111. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1111

[ix] World Health Organization (WHO). (n.d.). Air quality, energy and health. https://www.who.int/teams/environment-climate-change-and-health/air-quality-energy-and-health

[x] Shitova, Y. Y. (2024). The impact of long-distance travel to work on the health of commuting labour migrants: A literature review. Population and Economics, 8(1), 37-51. https://doi.org/10.3897/popecon.8.e109997

[xi] Hoehner, C. M., et al. (2012). Commuting distance, cardiorespiratory fitness, and metabolic risk. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 42(6), 571-578. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.020

[xii] Scrivano, L., Tessari, A., Marcora, S., Manners, D. (2023). Active mobility and mental health: A scoping review towards a healthier world. Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health. 11. 1-44. 10.1017/gmh.2023.74.

[xiii] Olszewska-Guizzo, A., Fogel, A., Benjumea, D., Tahsin, N. (2022). Sustainable Solutions in Urban Health: Transdisciplinary Directions in Urban Planning for Global Public Health. In: Leal Filho, W., Vidal, D.G., Dinis, M.A.P., Dias, R.C. (eds) Sustainable Policies and Practices in Energy, Environment and Health Research. World Sustainability Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86304-3_14.

[xiv] Evans, G. W., & Wener, R. E. (2007). Crowding and personal space invasion on the train: Please don't make me sit in the middle. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 27(1), 90-94. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2006.10.002

[xv] Glover, V., et al. (2018). The role of overcrowding in the urban mental health crisis. Journal of Urban Health, 95(4), 487-499. doi:10.1007/s11524-018-0288-0

[xvi] Zhang, Z., Měchurová, K., Resch, B., Amegbor, P. M., Sabel, C. (2023). Assessing the association between overcrowding and human physiological stress response in different urban contexts: a case study in Salzburg, Austria. International Journal of Health Geographics. 22. 10.1186/s12942-023-00334-7.

[xvii] Olszewska-Guizzo, A., Fogel, A., Benjumea, D., Tahsin, N. (2022). Sustainable Solutions in Urban Health: Transdisciplinary Directions in Urban Planning for Global Public Health. In: Leal Filho, W., Vidal, D.G., Dinis, M.A.P., Dias, R.C. (eds) Sustainable Policies and Practices in Energy, Environment and Health Research. World Sustainability Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86304-3_14.

[xviii] Olszewska-Guizzo, A., Fogel, A., Benjumea, D., Tahsin, N. (2022). Sustainable Solutions in Urban Health: Transdisciplinary Directions in Urban Planning for Global Public Health. In: Leal Filho, W., Vidal, D.G., Dinis, M.A.P., Dias, R.C. (eds) Sustainable Policies and Practices in Energy, Environment and Health Research. World Sustainability Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86304-3_14.

[xix] Olszewska-Guizzo, A., Fogel, A., Benjumea, D., Tahsin, N. (2022). Sustainable Solutions in Urban Health: Transdisciplinary Directions in Urban Planning for Global Public Health. In: Leal Filho, W., Vidal, D.G., Dinis, M.A.P., Dias, R.C. (eds) Sustainable Policies and Practices in Energy, Environment and Health Research. World Sustainability Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86304-3_14.

[xx] Kumar, P., Brander, L., Kumar, M., & Cuijpers, P. (2023). Planetary Health and Mental Health Nexus: Benefit of Environmental Management. Annals of global health, 89(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.4079.

[xxi] Kabisch, N. Basu, S., Van den Bosch, M., Bratman, G., Masztalerz, O. (2023). Nature-based solutions and mental health. 10.4337/9781800376762.00019.

[xxii] Coombs, N. C., Meriwether, W. E., Caringi, J., & Newcomer, S. R. (2021). Barriers to healthcare access among U.S. adults with mental health challenges: A population-based study. SSM - population health, 15, 100847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100847

[xxiii] Alexander Haslam, S., et al. (2023). Connecting to Community: A Social Identity Approach to Neighborhood Mental Health. Personality and Social Psychology Review. doi.org/10.1177/10888683231216136.

[xxiv] Alexander Haslam, S., et al. (2023). Connecting to Community: A Social Identity Approach to Neighborhood Mental Health. Personality and Social Psychology Review. doi.org/10.1177/10888683231216136.

[xxv] Olszewska-Guizzo, A. (2023). Neuroscience for designing green spaces: Contemplative landscapes. Routledge.