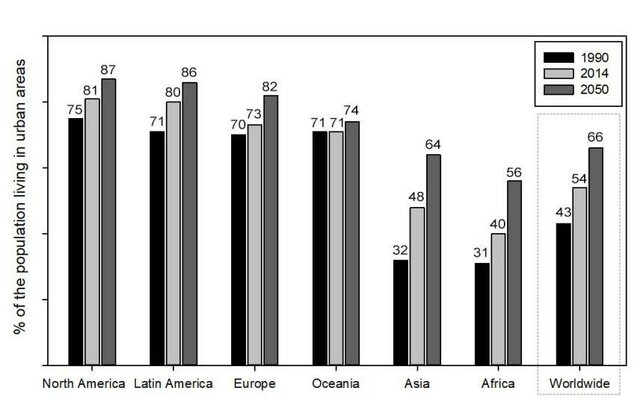

“The future of humanity is undoubtedly urban,” warns the UN-Habitat in their World Cities Report (2022), urging public health policies to address the growing health risks associated with urban expansion. Urban environments — characterized by traffic, pollution, noise, and overcrowding — not only create fertile ground for physical health issues but also place a significant burden on the mental health of their citizens (Olszewska-Guizzo et al., 2023). Neuropsychiatric diseases now account for 19.5% of all disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), while depression is responsible for 6.2% of DALYs (World Health Organization, n.d.). These mental health challenges deteriorate citizens’ quality of life and generate serious economic losses for the state.

Governments are increasingly recognizing the urgent need for interdisciplinary, evidence-based solutions to address this mental health crisis (Gruebner et al., 2017). A growing body of research highlights the restorative effects that contact with nature has on human health (Olszewska-Guizzo, Sia, & Escoffier, 2023). These effects include reducing stress and fatigue, triggering positive emotions, and improving cognitive functions such as concentration, memory, and creative performance (WHO, 2021).

Nature-based Solutions (NBS) are emerging as effective and cost-efficient strategies for addressing the growing mental health challenges in urban environments. The IUCN defines NBSs as actions to protect, sustainably manage, and restore natural or human-modified ecosystems, offering benefits for both environmental preservation and human well-being. Adopting NBSs to confront human health challenges arising from unhealthy environments aligns with the One Health approach (WHO) — which recognizes the interdependence of animal, ecosystem, and human health — and the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. NBSs have been well-documented to support people’s emotional, mental, and physical health by adopting a holistic approach to prevention, promotion, rehabilitation, and therapy.

Not Just Green

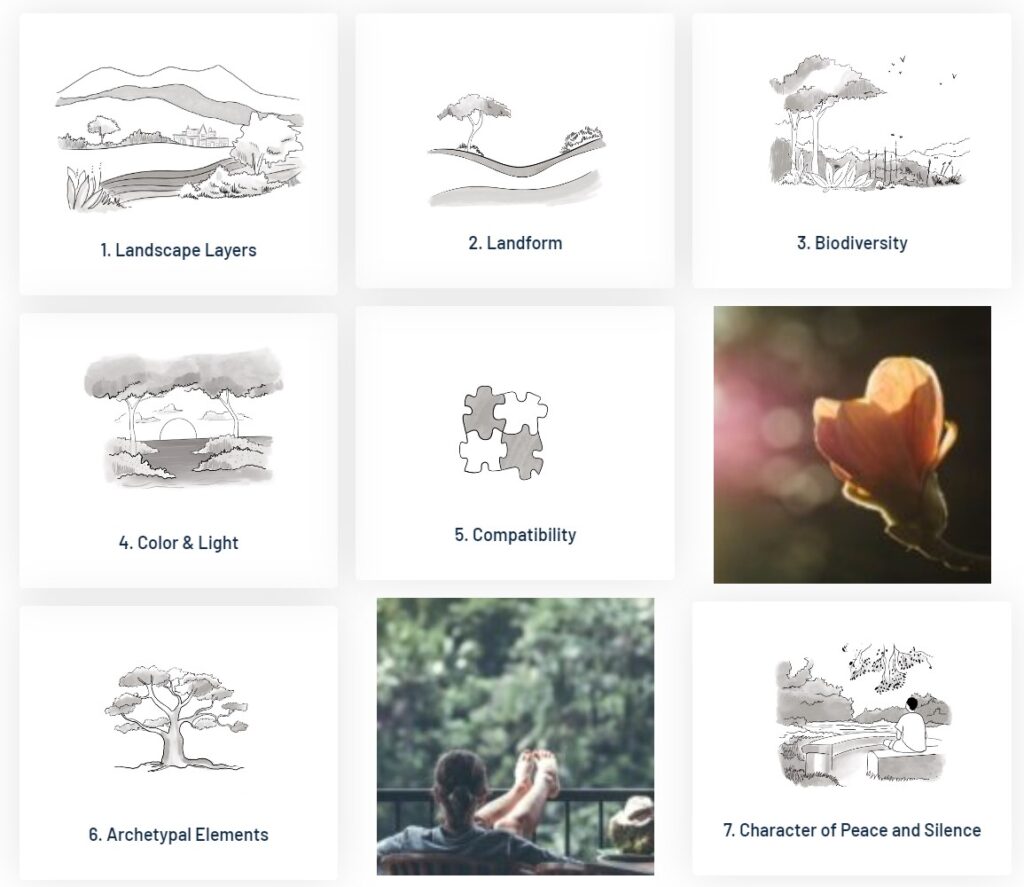

Often there is limited space available in cities for green areas, so it is important to optimize the design and use of the available green spaces (Olszewska-Guizzo, Sia, Fogel, et al., 2022). Urban planners, landscape architects, and conservation experts need to understand which types and characteristics of urban green spaces (UGS) most effectively benefit citizens’ mental health. This challenge inspired the development of the Contemplative Landscape Model (CLM) in 2016. The CLM measures how different landscape scenes can positively influence mental health through passive exposure. It focuses on landscape components that, when combined, trigger low-frequency brain activity associated with decreased cognitive strain, increased relaxation, and positive affect, as well as positive effects on mood and anxiety disorders(Olszewska-Guizzo, Sia, Escoffier, 2023).

The CLM evaluates landscape scenes based on seven key-components, each of which is rated using a 1–6-point scale. The final CLM score, the average of the seven key-components, provides a comprehensive assessment of a landscape's potential to offer beneficial mental health outcomes. The CLM is increasingly being used by practitioners to bridge the gap between landscape design and evidence-based impacts on mental health. It is also helping policy-makers make informed decisions on how to effectively curate UGSs to improve the mental health of their communities.

The main advantages of using the CLM include:

- Accessibility and Ease of Use: The tool can be easily learned following formal training and applied by urban design practitioners, landscape architects, and those with a keen eye for landscapes.

- Accuracy: The final CLM score is an average from the seven key landscape components in a single view or at multiple sites across the area, which helps to eliminate human error.

- Cost-effectiveness: The CLM requires minimal equipment. Evaluations can be conducted in a single site visit using tablets or just pen and paper.

- Efficiency: CLM also works with digital representations of landscapes (photos or videos) to save time, making it ideal for practitioners needing to assess multiple sites.

- Versatility: The CLM can be applied to a wide range of sites, including urban, suburban and rural spaces, making it a useful tool for diverse environments, and scales.

- Dual-purpose: The CLM can be used as an evaluation/ audit tool for green spaces, but also as a set of design guidelines to develop new creative mentally-healthy environments.

Global Examples: Singapore

The CLM has received increasing attention among professionals and researchers worldwide and is slowly finding its place in nature-based health promotion policies. The first country to adopt the CLM in its urban greening initiatives was Singapore. The National Parks Board (NParks) recognized the value of the evidence-based approach early, as part of their City in Nature initiative, which aims to ensure that the available green spaces are designed optimally to maximize the well-being of citizens across a diverse demographic, from the elderly and hospital patients to children with special needs.

The research conducted in Singapore, in collaboration with NParks and the National University of Singapore, found that therapeutic gardens with contemplative features contribute positively to a person's mental health and overall well-being. They also concluded that there were positive neuro-psychophysiological benefits from passive exposure to a therapeutic garden for the mental health of individuals with clinically concerning depressive disorders (Olszewska-Guizzo et al., 2022; Olszewska-Guizzo, Sia, Fogel, Escoffier, & Dan, 2022).

Singapore established the network of 13 therapeutic gardens scattered across the city-state, with plans for an additional 7 to be completed by 2030. Each garden is designed according to the contemplative landscape guidelines to encourage visitors to enjoy everyday contact with the salutogenic nature of the premises.

NParks’ efforts go beyond transforming parks and are slowly moving into the wider urban environment. There is a growing number of public officers and professionals trained in use of CLM for landscape assessment and design (an example of a recent workshop). Their continued research into Nature-based Solutions integrating CLM aligns with Singapore’s healthcare transformation plan, Healthier SG, to promote preventive health strategies for the whole population. Singapore’s efforts are setting a powerful and inspiring example of how states can benefit from embracing Nature-based Solutions to create healthier communities while prioritizing evidence-based design of their available green spaces.

Global Examples: Sweden

Sweden is the second country to incorporate the Contemplative Landscape Model (CLM) into its national health policy as part of its Nature-based Rehabilitation (NBR) program. Alos known as the Skåne-model, or Naturunderstödd Rehabilitering (NUR), it launched in 2013, and is the first of its kind in the Nordic region. NUR is currently active in the southern region of Skåne County, with plans to expand throughout the rest of the country.

The program is founded on extensive research from the Alnarp Rehabilitation Garden, run by the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU) (Grahn & Pálsdóttir, 2021). It emphasizes the role of nature in aiding patients to recover from stress-related mental illnesses, specifically exhaustion syndrome, mild to moderate depression, and anxiety (Grahn, Pálsdóttir, Ottosson, & Jonsdottir, 2017). The program takes eight weeks and is run at selected rural properties across Skåne Region (Wissler & Pálsdóttir, 2024).

The NBR program supports the rural development goals by employing trained coordinators to deliver the nature-based interventions and services of the program on their premises. These interventions are designed with the following core objectives in mind:

1) Rehabilitation Focus: Aims to support the standard of care to improve physical, mental, and social health through nature-supported activities.

2) Nature-Infused “Awake Rest:” Focuses on relaxation and recovery in a peaceful, undemanding natural environment that promotes mental rejuvenation.

3) Integration of Meaningful Activities: Encourages daily tasks in natural settings, offering participants purposeful engagements that align with the day-to-day operations of the NBR provider.

NBR requires from providers to maintain the quality standards set by the program. These include both the day activities to be offered to the patients and the quality and design of the property's natural environment. The CLM has been introduced to the program as a tool of evaluation for the property's landscape and to provide a systematic approach to develop quality standards comparable between the properties.

In the summer of 2024, six of the eight current NBR providers’ properties in the Skåne region were evaluated by independent experts using the Contemplative Landscape Model (CLM). This was the first time the CLM was conducted on rural properties. Previously, the CLM was used almost exclusively on urban environments. For this evaluation, an average of 12 to 23 landscape views per rural property was scored based on site maps, and the average score was computed for each location. This evaluation was carried out in preparation for the fourth procurement phase of the NUR program. The satisfactory performance of the CLM in this new context demonstrates its versatility and reliability, further supporting Sweden's ongoing commitment to integrating Nature-Based Solutions into public health policy. Sweden is the first country in Europe to adopt the Contemplative Landscape Model (CLM) as part of its national health policy. The adoption reflects their commitment to innovative approaches, including evidence-based initiatives such as the Alnarp Rehabilitation Garden and therapeutic gardens for dementia patients(Pálsdóttir, Wissler, & Thorpert, 2024; Pálsdóttir, O'Brien, Poulsen, & Dolling, 2021), and highlights the country's leadership in promoting preventive health strategies through nature. Sweden's efforts are setting a model example for other European nations to follow in creating healthier, more resilient communities.

Final Thoughts

The path to sustainable (positive) urban futures requires “collaborative, well-coordinated and effective multilateral interventions” by cities and sub-national governments. The health and well-being of citizens are classified as a top priority by the WHO to build resilient cities. Cities must understand that it is no longer enough to “[build] back better” to meet the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development the New Urban Agenda. It is time to “[build] back differently.”

Improving citizens’ access to mental health programs and developing holistic strategies to address mental illness remains a key concern worldwide. Without transformative action, mental health problems will “contribute to human suffering, premature mortality, and social breakdown, and will slow down economic recovery.” Improving the mental health of communities is essential not only for enhancing the quality of life of individuals but also for the continued economic and social development of states.

Recognizing the health-promoting value of landscapes, by integration of the Contemplative Landscape Model (CLM) by countries like Singapore and Sweden highlights its potential as a vital tool in integrating Nature-Based Solutions into national public health policies. It is, therefore, crucial to continue educating governments and decision-makers across the globe on the impact of evidence-based landscape design on public health. Through continued collaboration, research, and innovation, the CLM can become a foundational tool for preventive health strategies, helping to promote healthier, happier, and more resilient communities across the globe.

Reference List

Grahn, P., & Pálsdóttir, A.-M. (2021). Does more time in a therapeutic garden lead to a faster return to work? A prospective cohort study of nature-based therapy, exploring the relationship between dose and response in the rehabilitation of long-term patients suffering from stress-related mental illness. International Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 9, 1000614. https://doi.org/10.4172/2329-9096.1000614

Grahn, P., Pálsdóttir, A.-M., Ottosson, J., & Jonsdottir, I. (2017). Longer nature-based rehabilitation may contribute to a faster return to work in patients with reactions to severe stress and/or depression. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(11), 1310. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14111310

International Union for Conservation of Nature. (n.d.). Nature-based solutions. https://iucn.org/our-work/nature-based-solutions

National Parks Board. (n.d.). City in nature. https://www.nparks.gov.sg/about-us/city-in-nature

Olszewska-Guizzo, A., Fogel, A., Escoffier, N., Sia, A., Nakazawa, K., Kumagai, A., Dan, I., & Ho, R. (2022). Therapeutic garden with contemplative features induces desirable changes in mood and brain activity in depressed adults. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.757056

Olszewska-Guizzo, A., Russo, A., Roberts, A. C., Kühn, S., Marques, B., Tawil, N., & Ho, R. C. (2023). Editorial: Cities and mental health. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1263305. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1263305

Olszewska-Guizzo, A., Sia, A., Fogel, A., Escoffier, N., & Dan, I. (2022). Features of urban green spaces associated with positive emotions, mindfulness, and relaxation. Scientific Reports, 12, 20695. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-24637-0

Olszewska-Guizzo, A., Sia, A., & Escoffier, N. (2023). Revised contemplative landscape model (CLM): A reliable and valid evaluation tool for mental health-promoting urban green spaces. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 86, 128016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2023.128016

Pálsdóttir, A.-M., O'Brien, L., Poulsen, D., & Dolling, A. (2021). Exploring migrants’ sense of belonging through participation in an urban agricultural vocational training program in Sweden. Journal of Therapeutic Horticulture, 31(1), 11.

Pálsdóttir, A. M., Wissler, S. K., & Thorpert, P. (2024). An innovative approach in research and development of clinical nature-based rehabilitation in health care and vocational training: The living laboratory, Alnarp rehabilitation garden. Landscape Architecture, 31(5), 116-123. https://doi.org/10.3724/j.fjyl.202404020196

Region Skåne. (n.d.). Naturunderstödd rehabilitering. https://vardgivare.skane.se/vardriktlinjer/forsakringsmedicin/naturunderstodd-rehabilitering/

UN-Habitat. (2022). World cities report 2022: Envisaging the future of cities. United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat). https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2022/06/wcr_2022.pdf

United Nations. (n.d.). The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda

Wissler, S. K., & Pálsdóttir, A. M. (2024). A quality assurance framework for outdoor environments, facilities, and program standards in nature-based rehabilitation. Landscape Architecture, 31(5), 91-102. https://doi.org/10.3724/j.fjyl.202312140567

World Health Organization. (2021). Mental health promotion and mental disorders prevention: Framework for a comprehensive mental health strategy in Europe. WHO Regional Office for Europe. https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289055666

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Global health estimates: Leading causes of DALYs. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/global-health-estimates-leading-causes-of-dalys

World Health Organization. (n.d.). One Health. https://www.who.int/health-topics/one-health#tab=tab_1