Dr Bruno Marques is a landscape architect and educator. He completed his Landscape Architecture studies at the University of Lisbon (Portugal) and Berlin Technical University (Germany), followed by his PhD studies at the University of Otago (New Zealand). Bruno has practised in Germany, Estonia, the United Kingdom and New Zealand, having an extensive portfolio of Read More

Tag: communities

Nature in Mind: An Interview with Dr. Anna María Pálsdóttir

Dr. Anna María Pálsdóttir is the Senior Lecturer/Assistant Professor in Environmental Psychology at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), the Department of People and Society. She is a professional horticulturist with a BSc in Biology & Horticulture Sciences and a MSc and PhD in Landscape Planning and Environmental Psychology. Dr. Pálsdóttir works with conceptual Read More

World Sustainability Forum Speech on Community-led Greenspace |13-15 September 2021

On Monday 13th September at 11:00 CEST Dr Diana Benjumea Meija presented her research on “The Spatial and Social Components of Community-led Green Spaces and its Contribution to the Health and Wellbeing of Low-income Communities” at the 9th World Sustainability Forum In the last decade, there has been a surge in projects initiated by urban Read More

Mental Health in Slums – the Case of Bangladesh Among Other Developing Countries

The share of the world’s population living in urban areas has been predicted to increase from 55% in 2018 to 60% in 2030 (UN, 2018). Every year people move to the urban areas from villages for various reasons. If we try to see this urban-rural migration under the push-pull model, push factors from rural end Read More

Urban Land Institute/Health Leaders Network

In early 2021 our Board Member and Lead researcher Dr Diana Benjumea was selected to join a prestigious Health Leaders Network initiated by the Urban Land Institute (ULI). Health Leaders Network is a platform aimed at sharing knowledge and ideas with health leaders across continents. It gathers professionals across the globe with the skills and Read More

EDRA52 Conference Presentation | Just Environments

Speech presented at the 25th Environmental Design Research Association 25th Conference in the panel “Green Resilience and Behaviour” by Nazwa Tahsin. Part of the Research Program “Nature Connection and Mental Health of Communities”. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hwGBP0sscNo&t=24s https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.edra.org/resource/resmgr/edra52/subpages/edra52_-_program_book.pdf

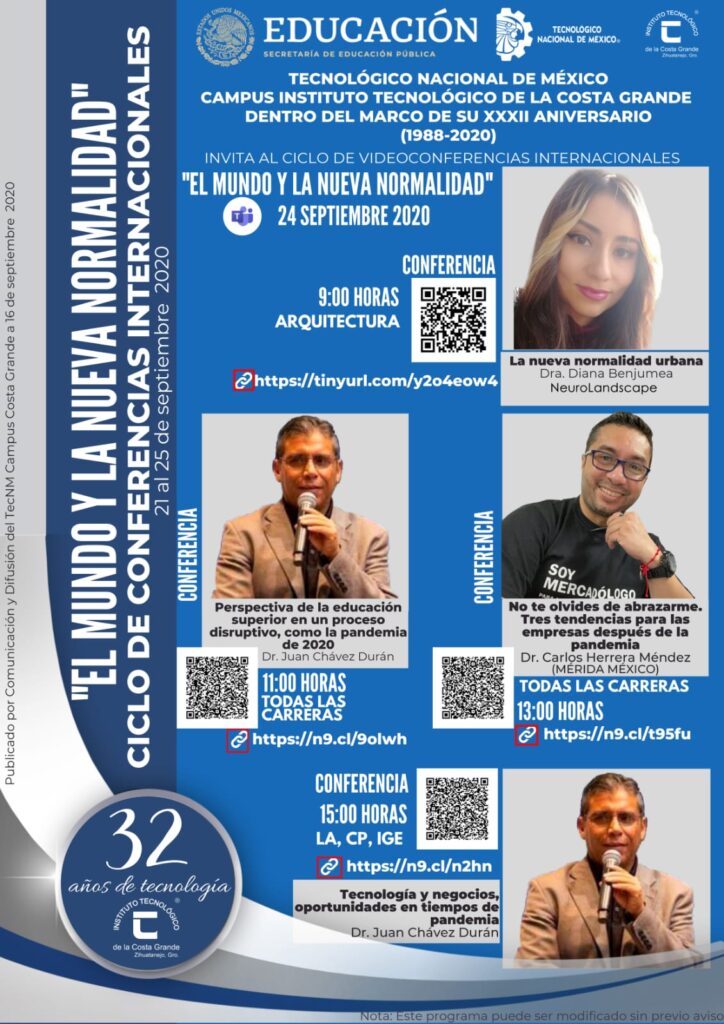

The New Urban Normal_Dr Diana’s speech at TecNM (Mexico)_VIDEO

24th September 2020. Tecnológico Nacional de México, campus Costa Grande, hosted an online event addressing the World New Normal in the interdisciplinary lens. Dr Diana Benjumea gave a speech regarding architecture and urban planning, where she sets a new paradigm of bottom-up, evidence-based urban design. Moreover, she introduces NeuroLandscape projects and explains the global implications Read More

Connecting Social and Urban Studies with Health and Well-being of Communities – Speech at the National University of Colombia in Manizales

On January 29th 2020 NeuroLandscape’s Board Member Dr. Diana Benjumea was invited to give a talk in the Universidad Nacional de Colombia to the staff and students of the Department of Architecture and Built Environment in the city of Manizales. The talk aimed to share the multidisciplinary work that is conducted in NeuroLandscape with special Read More