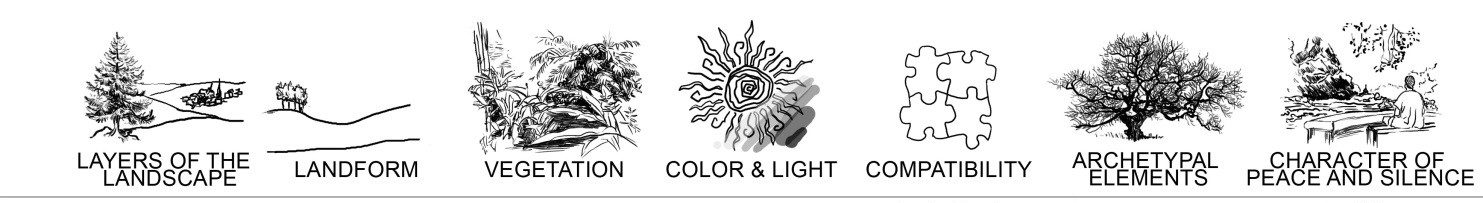

One of the core questions in our quest for making landscapes more contemplative have been identifying what actually makes a space contemplative or not. Having discussed the importance of long-distance views in an earlier post (click here), today, we turn to a characteristic under the label ‘landform’ in defining a contemplativeness of landscape. So what hides under this category?

In a way, we can say we continue looking out into the distance, as was true in the first category we introduced. The landform category is based on contemplative features such as smoothness of the ground and manipulation of the skyline (through opening and closings of views, as well as through introducing some specific elements of the skyline) to stimulate looking up to the sky. This suggests that the subtle hills and mounds and diversified skyline would be the most desired for contemplation, thus flat or rugged landforms are expected to be weaker in the classification of their contemplativeness.

Since there are no sharp edges or geometric figures in the natural world, smooth shapes remind us of the structures created by nature. Not only does mimicking nature in designed landscapes satisfy our need to reconnect with nature, but it is also considered the highest masterpiece of design:

[…] Growth of the vision and contemplation of nature enables him [a designer] to rise towards a metaphysical view of the world and to form free abstract structures which surpass schematic intention and achieve a new naturalness of the work. Then he creates a work … that is the image of God’s work (Klee, 1923, p. 17).

Forms inspired by nature are very familiar to us psychologically as we all come from nature, and are marked with bio-preference, namely biophilia. In other words, we all love nature on a deep psychological level. Environments rich in natural views and imagery reduce our stress, enhance focus and concentration, and have restorative benefits as proven in research by environmental psychologists (James, 1892, 1984; Kaplan & Kaplan, 1982). Not only does actual contact with nature count, but even contact with different types of representations of it, such as posters, window views or nature-like sculptures, are sufficient to induce the biophilia effect (Kaplan & Kaplan, 1995).

Having said that, though, “too much of nature” is not preferred. Places that are too wild or without identity will not make us feel safe. We have evolved in such a way that we don’t feel comfortable in wilderness untouched by human hands. Our evolution made us adapt to spaces where the wilderness is under control, moderated and maintained, similar to natural reserves, parks, and urban gardens. Research on landscape preference has shown that people prefer scenes with ‘tamed nature’ over ‘wild nature’’, where human intervention such as mown grass, boardwalks, and bridges are present (Kaplan et al., 1998). We also have a preference for “smooth ground” with an undulating, moundy form. Hermann, in his description of the Woodland Cemetery in Stockholm (see image below) as the example of the most contemplative landscape design, seems to confirm this statement. He describes the soothing and peaceful character provided by leveling and smoothing over the ground, creating a large clearing with an elevated heart of the cemetery called Meditation Grove:

The ground here is a continuous blanket of surprisingly lush green lawn (Hermann, 2005, p. 56).

Another interesting design strategy that purportedly triggers the contemplative response is connected with looking at the sky and its vastness, due to its “coolness and distant serenity” (Zelanski & Fisher, 1996, p. 236). In every outdoor space, the sky is the ceiling and the atmosphere of Earth is the huge dome of every landscape. Looking towards the sky delivers the longest view and a feeling of vastness. This is why looking up to the sky, watching the sunset or moving clouds, and observation of stars at night has been connected to contemplation.

While the sky itself is not an element that can be designed, the designer can certainly use some particular tricks to stimulate the visitor to look up at the skyline (Hermann, 2005). The viewer can be stimulated to look up at the sky by managing the level of the point of view. If focal-designed elements are located above the head of the viewer, they will usually look up automatically. The easiest way to change the point of view is to sit down, then while looking around we see much less sky, and much more ground, and if the designed elements and structure is leading our attention up, we will then look up (such as benches). Also, manipulating the skyline by inserting towering elements as opposed to a flat skyline is one strategy to make us look up. The design does not have to necessarily make us raise our heads in a large or small motion, what matters is managing the attention. It can be achieved by designing a mirror of still water in which the sky reflects (Hermann, 2005; Hou, 2015). This strategy is also connected to a strong archetype of water, and can be achieved in the designed landscape by implementing equipment that makes us sit back or lay with our eyes up towards the sky. Another trick is introducing hills, mounds and a viewpoint to achieve this particular effect.

To show a clear example of how this works in practice, let us leave you with the final image straight from the Teletubbies. The landscape with smooth undulating landform and mounds has a ‘safe haven’ sort of air about it, with calming effects for children… and adults alike.

Based on Olszewska, A. (2016) “Contemplative Values of Urban Parks and Gardens Applying Neuroscience to Landscape Architecture”, PhD thesis, University of Porto, Portugal, with some parts quoted verbatim.

Other references:

Hermann, H. (2005). On the transcendent in landscapes of contemplation. In Contemporary Landscapes of Contemplation. Krinke, R. (Ed). 36-72.

Hou, R. (2015, January). From Beijing to Washington—A Contemplation in the Concept of Municipal Planning. In Symposium on Chinese Historical Geography (pp. 61- 82). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

James, W. (1892). A plea for psychology as a'natural science'. The Philosophical Review, 1(2), 146-153.

Kaplan, S., & Kaplan, R. (1982). Cognition and Environment: Functioning in an Uncertain World.

Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: T oward an integrative framework. Journal of environmental psychology, 15(3), 169-182.

Kaplan, R., Kaplan, S., & Ryan, R. (1998).With people in mind: Design and management of everyday nature. Washington DC: Island Press.

Klee, P. (1923). Ways of Studying Nature, Lecture at the Bauhaus. New York, Roizzoli, 984, pp. 17-18

Zelanski, P. & Fisher, M. P. (1996). Design Principles & Problems. Brace College: New York.

Images:

- Toronto Skyline (2010), Photo by: Nicola Betts, Source: www.asla.org

- Singapore Botanic Gardens

- Woodland Cemetery in Stockholm (Landscape Architecture Works, Landezine)

- Teletubbies (source: www.wikia.com)