Contemplative Landscape Model and mental health

CLM is a tool for Urban Green Space visual quality evaluation, addressing the existing need for mitigating the burden of mental health resulting from urbanicity and filling the gaps in knowledge on UGS for mental health.

CLM measures the extent to which a given landscape view has the potential to positively influence the mental health and well-being of individuals passively exposed to them. According to its original premis the landscape components considered most contemplative, when aggregated within the scene, would trigger an increase in low frequency brain activity associated with momentary decreased cognitive strain, increased relaxation and positive affect during an act of just a passive observation of the landscape [1] This experience could balance out the opposite brain reactivity, arising with high information processing typical with the exposure to urbanized environments [2]. Such brain response patterns have been linked to number of conditions including mood and anxiety disorders [3]. Based on this evidence, we refer in what follows to these effects using the terms “salutogenic”, “positive mental health outcomes”, and “mental health and well-being”.

The goals of the CLM are to:

(1)- identify and evaluate the environments that promote mental health and well-being within cities, and to

(2) inform landscape design and urban planning practice with specific features and components of the UGS landscape scenery. The use of CLM is thoroughly described in the recent textbook “Neuroscience for Designing Green Spaces: Contemplative Landscapes” [4].

Contemplative Landscape Model: Background and Characteristics

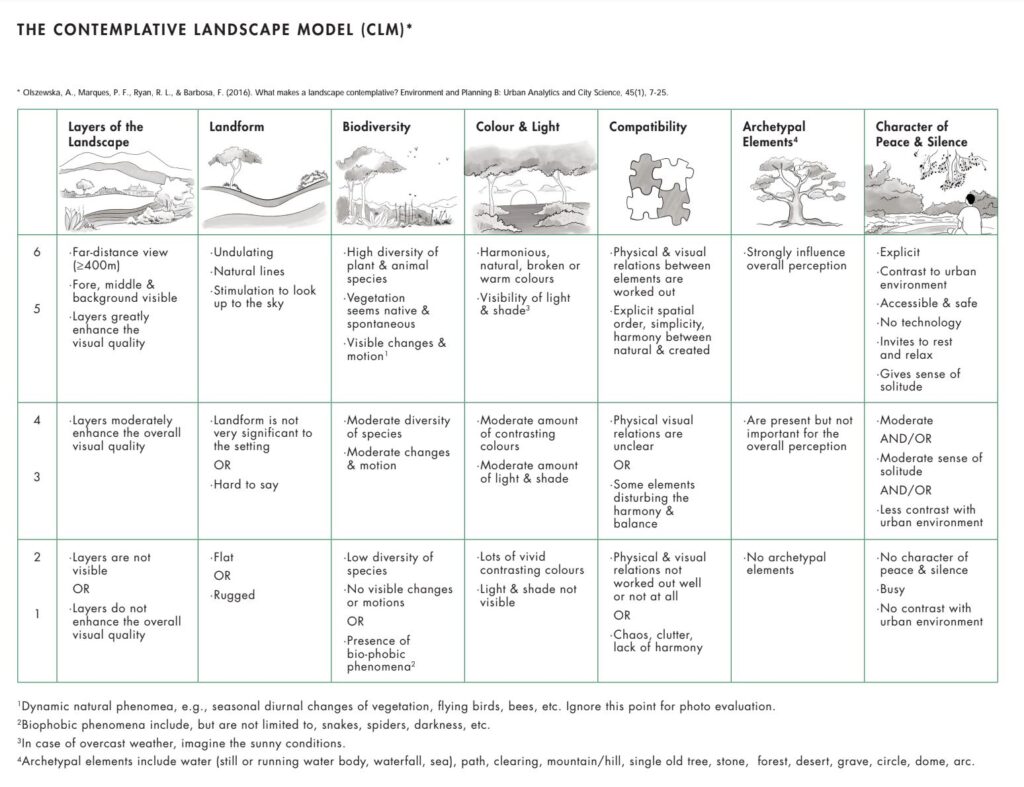

As an expert-based tool, it requires its users to have received formal training in landscape architecture, architecture, or urban design disciplines. The object of the assessment is a landscape scene as perceived by the human eye. It can therefore be an actual onsite view or a photographic or videographic representation for off-site assessment. CLM consists of seven items: (1) Layers of the Landscape, (2) Landform, (3) Biodiversity, (4) Color and Light, (5) Compatibility, (6) Archetypal Elements and (7) Character of Peace and Silence, to be assessed using a 1-6-point scale. The overall CLM score is the average of the score of these seven sub-categories.

Contemplative_Landscape_Model_II (download & print)

The CLM is rooted in traditions of early urban parks design while being informed by an evidence-based approach. Its items were determined based on extensive literature review, including studies on previous frameworks of landscape design theory and aesthetics. The focus of CLM on the qualities of individual scenery echoes the concepts of early landscape architecture theory, when it was believed that specific aspects of natural scenery can have strong “curative value” (Beveridge & Rocheleau, 1995). Frederick Law Olmsted, known as the “father of landscape architecture,” already in the 19th century believed in the salutogenic power of urban parks, driven by the elements and features in their scenery. He also believed that the benefits from these scenery exposures are delivered unconsciously. In one of his texts, he wrote:

“…the highest value of a park must be expected to lie in elements and qualities of scenery to which the mind of those benefitting by them is liable, at the time the benefit is received, to give little conscious cogitation” (Olmsted, 1881, p. 365).

The CLM has received increasing interest over the years among professionals and researchers. Most notably, it was acknowledged by the National Parks Board in Singapore in their urban greening for health agenda [4], and has been utilized by researchers and professionals (e.g.[5][6][7]).

References:

- Olszewska-Guizzo, A., Fogel, A., Escoffier, N., Sia, A., Nakazawa, K., Kumagai, A., Dan, I., & Ho, R. (2022). Therapeutic Garden With Contemplative Features Induces Desirable Changes in Mood and Brain Activity in Depressed Adults [Original Research]. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.757056

- Olszewska-Guizzo, A., Fogel, A., Benjumea, D., & Tahsin, N. (2022). Sustainable Solutions in Urban Health: Transdisciplinary Directions in Urban Planning for Global Public Health. In Sustainable Policies and Practices in Energy, Environment and Health Research (pp. 223-243). Springer.

- Ancora, L. A., Blanco-Mora, D. A., Alves, I., Bonifácio, A., Morgado, P., & Miranda, B. (2022). Cities and neuroscience research: A systematic literature review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13.

- Olszewska-Guizzo, A. (2023). Neuroscience for Designing Green Spaces: Contemplative Landscapes. Taylor & Francis.

- Sia, A., Tan, P. Y., & Er, K. B. H. (2023). The contributions of urban horticulture to cities’ liveability and resilience: Insights from Singapore. Plants, People, Planet.

- Sia, A., Tan, P. Y., Kim, Y. J., & Er, K. B. H. (2023). Use and non-use of parks are dictated by nature orientation, perceived accessibility and social norm which manifest in a continuum. Landscape and Urban Planning, 235, 104758.

- Salleh, M., Othman, N., Malek, N., Mohamed, N., & Zainal, M. (2021). Prospects of contemplative urban park from expert perspectives. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science.

- Yanru, H., Masoudi, M., Chadala, A., & Olszewska-Guizzo, A. (2020). Visual Quality Assessment of Urban Scenes with the Contemplative Landscape Model: Evidence from a Compact City Downtown Core. Remote Sensing, 12(21), 3517